aki no no ni

sakitaru hana o

yubi orite

kaki kazoureba

nana kusa no hana.

hagi ga hana

obana kuzubana

nadeshiko no hana

ominaeshi

mata fujibakama

asagao no hana.

---------------------

Flowers blossoming

in autumn fields -

when I count them on my fingers

they then number seven

The flowers of bush clover,

eulalia, arrowroot,

pink, patrinia,

also, mistflower

and morning faces flower.

Yamanoue Okura (C. 660 - 733)

Manyoshu: 8:1537-8

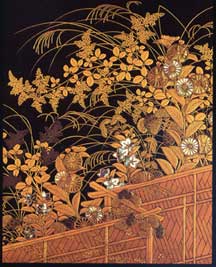

Autumn brings with it a certain sadness at the passing

of fair summer days and the coming of cold winter. It also

brings a beauty celebrated throughout the world. Autumn

is a time when mountains turn to magnificent crimson tapestries

and cities glow in wonderful autumnal tints as days grow

cooler. Autumn has long been particularly extolled in Japanese

poetry, painting, and design.

The

seven grasses of autumn (aki no nanakusa)

were often mentioned in verses of the Manyoshu,

the earliest collection of Japanese poetry and song. Images

of autumn grasses in a later anthology of court poetry,

the Kokinshu, illustrate the culture of Heian

Japan [784 - 1185] in a way that could not be captured

by painting. Powerful and concise language draws out the

subtle nuances of life and love at the time, just as nature

and flowers invoke the mutable seasons of interior emotion. The

seven grasses of autumn (aki no nanakusa)

were often mentioned in verses of the Manyoshu,

the earliest collection of Japanese poetry and song. Images

of autumn grasses in a later anthology of court poetry,

the Kokinshu, illustrate the culture of Heian

Japan [784 - 1185] in a way that could not be captured

by painting. Powerful and concise language draws out the

subtle nuances of life and love at the time, just as nature

and flowers invoke the mutable seasons of interior emotion.

It is through Yamanoue Okura’s coupled

verse above that the seven autumn grasses gained renowned.

While it is uncertain who grouped these grasses together

for the first time, they have indeed become deeply rooted

in Japan’s daily life and history. Their presence

in the gardens of the Heian aristocracy may well have been

a great source of poetic inspiration, and still today grace

gardens and fields.

The

first mentioned bush clover (hagi or Lespedeza

japonica) appears over one hundred times in the Manyoshu,

making it the most well known of the autumn grasses. A deciduous

shrub of the pea family, bush clover can be found growing

wild in fields and mountains in Japan. Although most of

the seven grasses were not eaten, in olden times the seeds

of hagi were ground and mixed with rice gruel, while the

leaves were used as a substitute for tea. The arch of its

long, overhanging branches laden with reddish-purple flowers

and swaying in the wind makes an indelible impression. The

delicate flowers scatter as soon as crisp autumn breezes

begin. In The Tale of Genji, an early eleventh

century novel which has been called the greatest work in

Japanese literature, as Genji’s wife Murasaki lies

on her deathbed, she is visited by Genji and his daughter,

the empress. Their thoughts move to the hagi growing in

Murasaki’s garden as they make final farewells. A

corresponding scene in a 12th century Illustrated Tale

of Genji handscroll shows Genji, Murasaki, and the

empress in a room on the right of the picture while hagi

petals float away with the wind on the left. The

first mentioned bush clover (hagi or Lespedeza

japonica) appears over one hundred times in the Manyoshu,

making it the most well known of the autumn grasses. A deciduous

shrub of the pea family, bush clover can be found growing

wild in fields and mountains in Japan. Although most of

the seven grasses were not eaten, in olden times the seeds

of hagi were ground and mixed with rice gruel, while the

leaves were used as a substitute for tea. The arch of its

long, overhanging branches laden with reddish-purple flowers

and swaying in the wind makes an indelible impression. The

delicate flowers scatter as soon as crisp autumn breezes

begin. In The Tale of Genji, an early eleventh

century novel which has been called the greatest work in

Japanese literature, as Genji’s wife Murasaki lies

on her deathbed, she is visited by Genji and his daughter,

the empress. Their thoughts move to the hagi growing in

Murasaki’s garden as they make final farewells. A

corresponding scene in a 12th century Illustrated Tale

of Genji handscroll shows Genji, Murasaki, and the

empress in a room on the right of the picture while hagi

petals float away with the wind on the left.

The

second named susuki (eulalia or Miscanthus

sinensis) is sometimes called obana or

‘tail flower’ because its feathery white flower

looks like an animal’s tail when it blooms in early

autumn. A well known Zen phrase describes this scene, “A

white horse enters a tail flower field (hakuba roka

ni iru). From a distance the two are indistinguishable,

yet the white horse remains the white horse, the tail flower,

tail flower--an illustration of the Zen paradox of not one,

not two. Closely associated with the autumn moon, the silver

tassels of susuki tossing in the wind have become inseparable

from the ambiance of the moonlit sky. Growing to heights

of sixty inches or more, this perennial herb of the Graminae

family grows wild on the hills and fields of Japan and other

East Asian countries. The well known poetic reference to

the Plains of Musashi or Musashino conjures images of a

vast distance overgrown with plumes of susuki as far as

the eye can see. The

second named susuki (eulalia or Miscanthus

sinensis) is sometimes called obana or

‘tail flower’ because its feathery white flower

looks like an animal’s tail when it blooms in early

autumn. A well known Zen phrase describes this scene, “A

white horse enters a tail flower field (hakuba roka

ni iru). From a distance the two are indistinguishable,

yet the white horse remains the white horse, the tail flower,

tail flower--an illustration of the Zen paradox of not one,

not two. Closely associated with the autumn moon, the silver

tassels of susuki tossing in the wind have become inseparable

from the ambiance of the moonlit sky. Growing to heights

of sixty inches or more, this perennial herb of the Graminae

family grows wild on the hills and fields of Japan and other

East Asian countries. The well known poetic reference to

the Plains of Musashi or Musashino conjures images of a

vast distance overgrown with plumes of susuki as far as

the eye can see.

The

only one of the seven grasses used in cooking is arrowroot

(kuzu, Pueraria lobata). Its root is pounded,

and the white starch that remains is dried, powdered, and

used as a thickening agent in many styles of cooking. A

summer sweet made from very thick kuzu is often served in

chanoyu. The kuzu plant is a perennial, herbaceous, climbing

vine of the pea family. It clusters thickly at forest edges,

producing reddish-purple flowers shaped like butterflies.

However it was the leaves of the plant most often noted

by poets and painters during the Heian period. Thick and

green on top, the underside is pale white. The beauty of

arrowroot leaves blowing in the wind was thought to be sublimely

white and pretty by Sei Shonagon, author of the 11th century

classic, The Pillow Book. The melancholy of its

fluttering leaves was also used to great expressive effect

in the Shrine in the Field (Nonomiya) chapter of The

Tale of Genji, as a woman whom Genji had loved separates

herself from the world. The

only one of the seven grasses used in cooking is arrowroot

(kuzu, Pueraria lobata). Its root is pounded,

and the white starch that remains is dried, powdered, and

used as a thickening agent in many styles of cooking. A

summer sweet made from very thick kuzu is often served in

chanoyu. The kuzu plant is a perennial, herbaceous, climbing

vine of the pea family. It clusters thickly at forest edges,

producing reddish-purple flowers shaped like butterflies.

However it was the leaves of the plant most often noted

by poets and painters during the Heian period. Thick and

green on top, the underside is pale white. The beauty of

arrowroot leaves blowing in the wind was thought to be sublimely

white and pretty by Sei Shonagon, author of the 11th century

classic, The Pillow Book. The melancholy of its

fluttering leaves was also used to great expressive effect

in the Shrine in the Field (Nonomiya) chapter of The

Tale of Genji, as a woman whom Genji had loved separates

herself from the world.

Nadeshiko

(Dianthus superbus, commonly called pink) is sometimes referred

to as wild carnation because it looks like a delicate relation

of florists’ carnations. Small fringed petals, five

in number, cluster on thin stems. Usually pink in color,

white varieties also exist. In Japanese the name literally

means “an affectionate touch for a child,” indicating

how endearing this flower is. The Manyoshu treats

dianthus as both a summer and an autumn flower, but later

it appears almost exclusively in mid to late summer context.

Several varieties of nadeshiko may be found along riverbanks,

on fields of eulalia, by the ocean shore, and along bluffs.

Another frequent poetic reference for dianthus is tokonatsu,

although it has a more romantic connotation. Nadeshiko

(Dianthus superbus, commonly called pink) is sometimes referred

to as wild carnation because it looks like a delicate relation

of florists’ carnations. Small fringed petals, five

in number, cluster on thin stems. Usually pink in color,

white varieties also exist. In Japanese the name literally

means “an affectionate touch for a child,” indicating

how endearing this flower is. The Manyoshu treats

dianthus as both a summer and an autumn flower, but later

it appears almost exclusively in mid to late summer context.

Several varieties of nadeshiko may be found along riverbanks,

on fields of eulalia, by the ocean shore, and along bluffs.

Another frequent poetic reference for dianthus is tokonatsu,

although it has a more romantic connotation.

Ominaeshi

(Patrinia scabiosaefolia, patrinia), is a perennial herb

that grows in sunny fields of eulalia and mountainous areas

extending from Japan to Korea, China, and Eastern Siberia.

Sometimes referred to as “maiden flower,” the

tall stems of the ominaeshi fan out symmetrically at the

top, bearing tiny five-petaled flowers that resemble miniature

parasols. In classic Japanese literature, the flower’s

gentle appearance was likened to a beautiful woman and again

has romantic overtones. Ominaeshi

(Patrinia scabiosaefolia, patrinia), is a perennial herb

that grows in sunny fields of eulalia and mountainous areas

extending from Japan to Korea, China, and Eastern Siberia.

Sometimes referred to as “maiden flower,” the

tall stems of the ominaeshi fan out symmetrically at the

top, bearing tiny five-petaled flowers that resemble miniature

parasols. In classic Japanese literature, the flower’s

gentle appearance was likened to a beautiful woman and again

has romantic overtones.

Fujibakama

(Eupatorium fortunei, hemp agrimony or mistflower), has

tiny white blossoms tinged with purple atop long stems.

Originating in China, it has been cultivated in Japan and

can be found along the upper ground of riverbanks. With

some similarities in appearance to ominaeshi, fujibakama

has a subtle fragrance, and the dried plant was worn as

a medicinal sachet. The literal translation is “purple

trousers.” Therefore reference to the flower in poetry

usually connotes a man rather than a woman. Many Kokinshu

poems about fujibakama allude to its fragrance being the

only momento left of a departed lover. Fujibakama

(Eupatorium fortunei, hemp agrimony or mistflower), has

tiny white blossoms tinged with purple atop long stems.

Originating in China, it has been cultivated in Japan and

can be found along the upper ground of riverbanks. With

some similarities in appearance to ominaeshi, fujibakama

has a subtle fragrance, and the dried plant was worn as

a medicinal sachet. The literal translation is “purple

trousers.” Therefore reference to the flower in poetry

usually connotes a man rather than a woman. Many Kokinshu

poems about fujibakama allude to its fragrance being the

only momento left of a departed lover.

The

last named of the autumn grasses is asagao.

Literally this translates as ‘morning face’ which

in its modern meaning designates the morning glory plant

(Ipomaea purpurea). This creeping plant with trumpet-shaped

blossoms was brought from the Nepalese Himalayas into China,

and then to Heian Japan. Its early cultivation in Japan

failed, but later flourished as the story about Sen Rikyu

and the morning glory garden proves. Rikyu’s canonical

use of morning glories in the tearoom has prompted all

later generations to refrain from imitation and to enjoy

their morning glories in the garden. The

last named of the autumn grasses is asagao.

Literally this translates as ‘morning face’ which

in its modern meaning designates the morning glory plant

(Ipomaea purpurea). This creeping plant with trumpet-shaped

blossoms was brought from the Nepalese Himalayas into China,

and then to Heian Japan. Its early cultivation in Japan

failed, but later flourished as the story about Sen Rikyu

and the morning glory garden proves. Rikyu’s canonical

use of morning glories in the tearoom has prompted all

later generations to refrain from imitation and to enjoy

their morning glories in the garden.

In

Okura’s Manyoshu poem on the seven grasses, as well

as in other Heian literature, the word ‘asagao’

in all likelihood refers to the kikyo (Platycodon

grandifilorum, Chinese bellflower or balloon flower). This

late summer and early autumn flower has five-pointed, purple

trumpet-shaped blossoms, and can be found growing wild in

grassy mountain highlands and in other temperate areas.

Other garden varieties of kikyo include white, pink, and

variegated hues. In

Okura’s Manyoshu poem on the seven grasses, as well

as in other Heian literature, the word ‘asagao’

in all likelihood refers to the kikyo (Platycodon

grandifilorum, Chinese bellflower or balloon flower). This

late summer and early autumn flower has five-pointed, purple

trumpet-shaped blossoms, and can be found growing wild in

grassy mountain highlands and in other temperate areas.

Other garden varieties of kikyo include white, pink, and

variegated hues.

A notable absence in the seven autumn grasses

is kiku (Chrysanthemum sinensis Makino,

chrysanthemum), but this flower is celebrated in its own

right at the festival of the ninth day of the ninth month

Choyo no sekku. The plant was not native to Japan and references

to it were found first in poetry written in Chinese by

Japanese court scholars. Thus it does not appear in the

Manyoshu anthology of Japanese poetry and song, However

chrysanthemum became an important motif in painting, literature,

and other works of art from the Heian period to the present

day.

The capacity of the autumn grasses for inspiring

deep emotion among people in olden days may be viewed through

their composite nature of beauty tinged with sadness. More

than flowers of any other season, autumn grasses washed

by rain and bent in the wind attain a beauty unsurpassed,

and this is the beauty of chabana.

|