|

Warm Topics for Hot Days

At this time of year, Mr. Raku's face assumes an otherworldly appearance. As you know, both black and red Raku teabowls are made. For creating the black bowls in particular, the charcoal fire and bellows are worked to bring the kiln to a temperature over 1200 degrees Fahrenheit. In this encounter with the flames, the intense heat transmits to the eyeglass frames of the near-sighted Mr. Raku as well, so that by the time the bowls are ready to be pulled from the kiln, his melted eyeglasses have completely changed his appearance. This indeed warm story occurs at the absolute peak of the summer heat. Raku fires clay which two generations earlier was reserved expressly for his sake. While technical knowledge is involved, his art in a deeper sense involves a pure heart. There are no such specious concerns as "in" and "out." Rather, his focus is like listening to the pulse of his family's blood course through the veins of his body. It is a sound impossible to slight or trifle with. This consciousness is not limited to Raku teabowls alone, but as Mr. Raku's house is not distant from Oiemoto's and therefore we have met many times, a close understanding of his consciousness—his posture—has been afforded me. That of the Ohi pottery in Kanazawa is similar. Furthermore, this consciousness is not confined to teabowls, but it is no doubt true that all objects created by the human hand possess to a great degree this pure-hearted concentration of which I just spoke. Witness that regardless of the fact that the worst conditions for working bamboo are encountered when it blossoms, once every 100 years it is said, flaws can never be detected in the bamboo ladles made by the master, Kuroda Shogen. This utmost exertion to produce the finest in spite of whatever unfavorable conditions is awe-inspiring. One might call it the specialist's sense of pride that precludes him or her from resorting to petty excuses or the like. A tea house in Nagoya which I visit every month for a gathering is located in a quiet, hilly section of the city. It is pleasant in good weather or rain. One time I found myself touching my hand to its well-seasoned earthen wall. I could not overlook the contrast with the bright, sunny garden. Although I have no specialized knowledge of architecture or landscaping, it is a fact that truly fine objects may be instinctively discerned. At my gesture, my friend who is responsible for the teahouse told me the following story about the earthen wall. "At the time the teahouse was built, a plentiful supply of exactly the same quality dry walling material was made up, and today it is still stored under the veranda. The earthen wall is a dominant feature in Japanese architectural spaces, and one that is most easily damaged. Yet one cannot refurbish earthen walls the way one can tatami. Because characteristics of color and texture are unique to each place, it is impossible to try to match them at some later date. Over the last few decades a section of wall here has been re-plastered, but I imagine you cannot tell where." At that time I became acutely aware of the spirit and dedication of the workers who built the teahouse. Setting aside a large supply of plastering earth was an act of unconditional and earnest consideration towards others by the plasterer. On the chance the need would arise, the craftsperson arranged so that future workers would not be discommoded, and so that the distinctive flavor of the teahouse could be preserved. The name of this plasterer is not known. But in these times, his story is one to be treasured. Worldly or reclusive, well known or without fame,

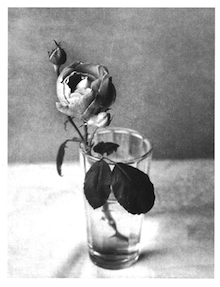

human life is like a tree of blooming flowers. Whether a flower

is taken in the hand of someone famous or it ends up blown to the

ground by the night wind, the essential beauty it possesses by virtue

of being a flower does not change. There is the rose tenderly treated

by Rilke's hand, which is the source of his verse, and then there

may be a rose which, without even having given comfort to the sick,

withers at the head of the sickbed. I cannot divine if either bloom

is happy, but within the limitations of purely poetical speculation,

human nature surely draws everyone to want to be like the bloom

in the hand of Rilke. While I myself am unable to answer the implications

of what is elevating and what is abasing, that which may be said

to strengthen the heart is truly born when human beings restrain

their most mortal passions. This is not a call for Puritanism. But

it is simply to say that to perceive the beauty of a flower quietly

nourishing itself with fresh water would be a good beginning. Translated by Christy A. Bartlett.

|

|